This post is part 1 of a series based on a talk I gave at the IH Barcelona conference on February 8th.

Exam classes always run the risk of ending up the same: with testing, testing and more testing. Whether it’s bad planning, midterm exhaustion, pre-exam pressure from students (is this gonna be on the test?) or simply course books and materials that don’t offer anything but testing, exam classes can sometimes devolve into doing one test prep task after another.

And exam prep listening lessons can often exhibit these tendencies in a more acute form.

Because listening is all in the head. You can’t see it. You, as in anybody, but especially you, the teacher. So how do you know if they’ve got it? You test them. So, as ELT listening expert John Field has written, all listening teaching tends to look like listening testing.

And I’d say it’s even worse in exam classes. When exam pressure and expectations of success come into play, everybody simply chases after the right answers. Did you put A or B? What was the answer? Did you get it right? Two plays, check your answers, and move on to the next task.

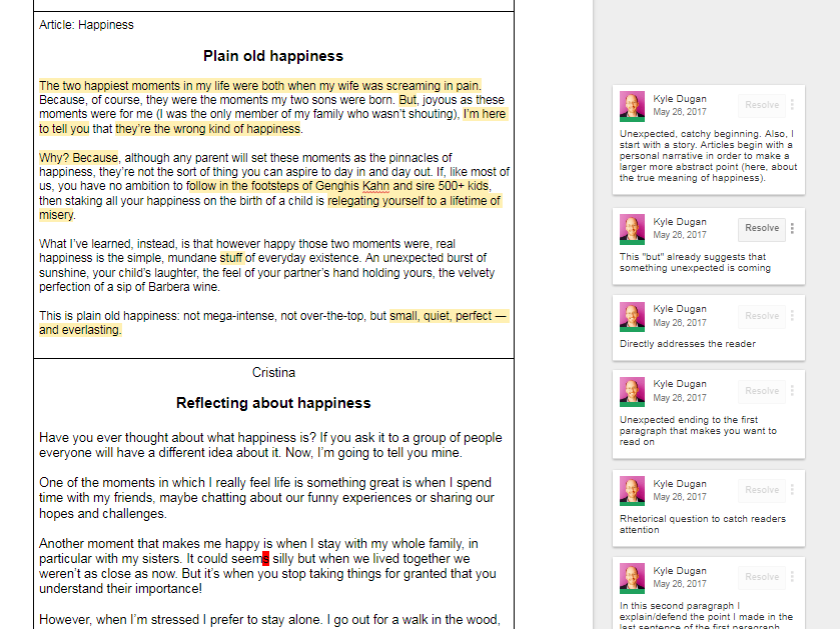

I teach mostly classes preparing students for the Cambridge First and Cambridge Advanced exams. While most test prep materials are good at teaching what Field calls (sneeringly, or so I always imagine) test-wise strategies, which he associates with exploiting loopholes, I’d more charitably call test-specific strategic competence. Students need to figure out the best way to approach each task, how to listen, how much time they have, and what they should do in their precious seconds of reading time.

But the reason Field sneers, of course, is that most of this doesn’t have anything to do with listening. It’s simply knowing and practicing the test.

But what students really need to succeed at listening is the ability to decode fairly fast speech – because without that they can’t begin to do the deeper operations of matching the audio signal to a written paraphrase (in the form of a test item) and distinguish it from similar-looking distractors.

Better decoding is essential. So how do you get better at decoding?

In this series of posts, I’m going to look at a couple of ways I try to help test takers get better at decoding, while (best of all) letting them turn on and tune into the stuff that interests them.

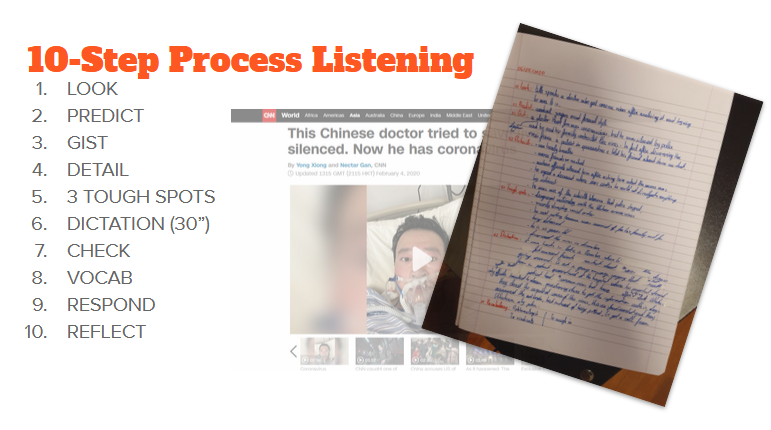

10-Step Process Listening

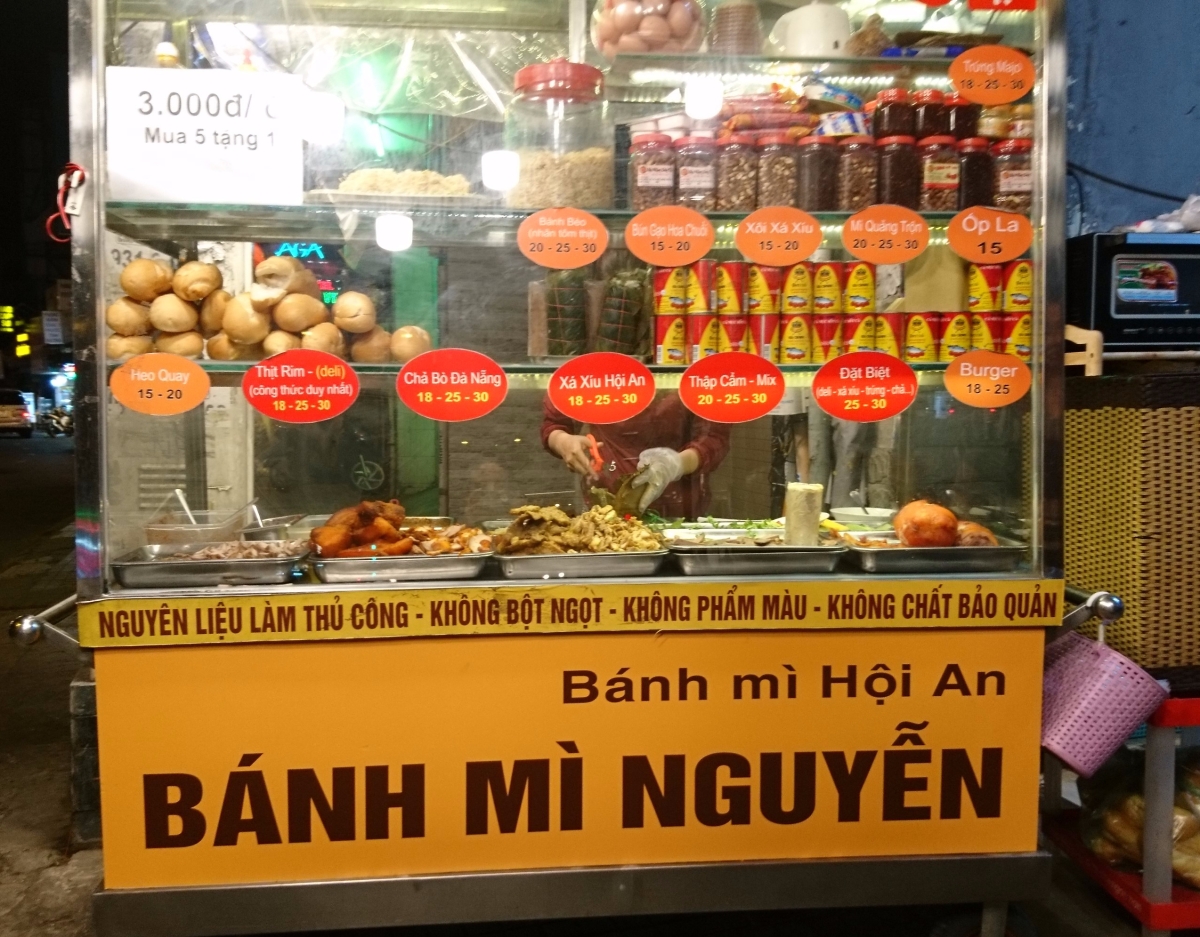

The upper intermediate and advanced level students – particularly teens – I teach all have their favorite YouTube channels and Netflix series that they watch in English. Do they understand them? Sure! Do they really understand them? Er, yeah?

Learners who can self-select YouTube audio usually get the gist, but there’s so much more they don’t. Listening tasks are designed to take them further into detail, but if you’re a busy teacher and you want them to listen to stuff beyond exam material, you probably won’t have time to make new tasks all the time.

That’s where a process comes in. Processes or routines are great because if you do it right you can give students something that’s materials light, learnable and repeatable (remember, like the PPP method you might have learned in your Celta course, but a whole lot better) and lets students work in relative autonomy.

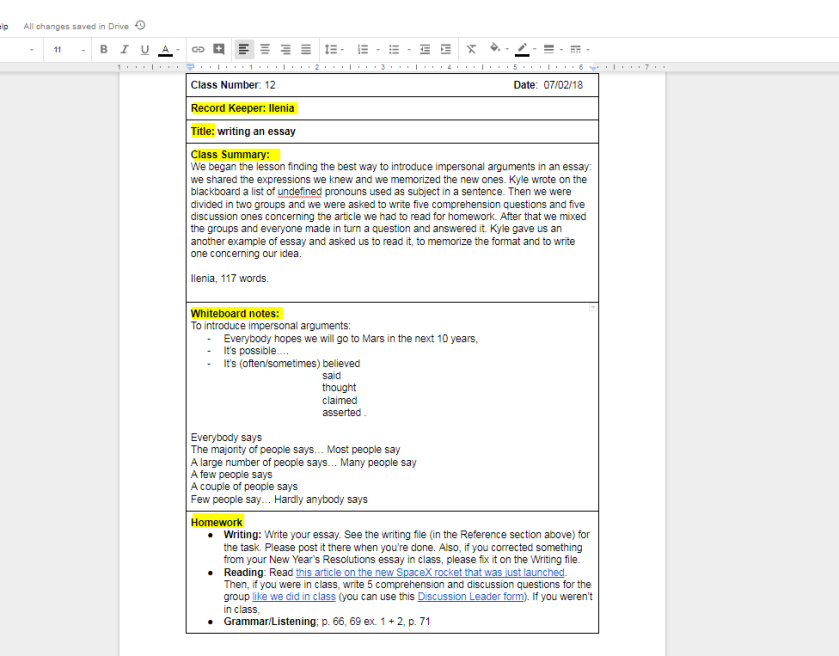

When students are faced with a video/audio text, here’s the process:

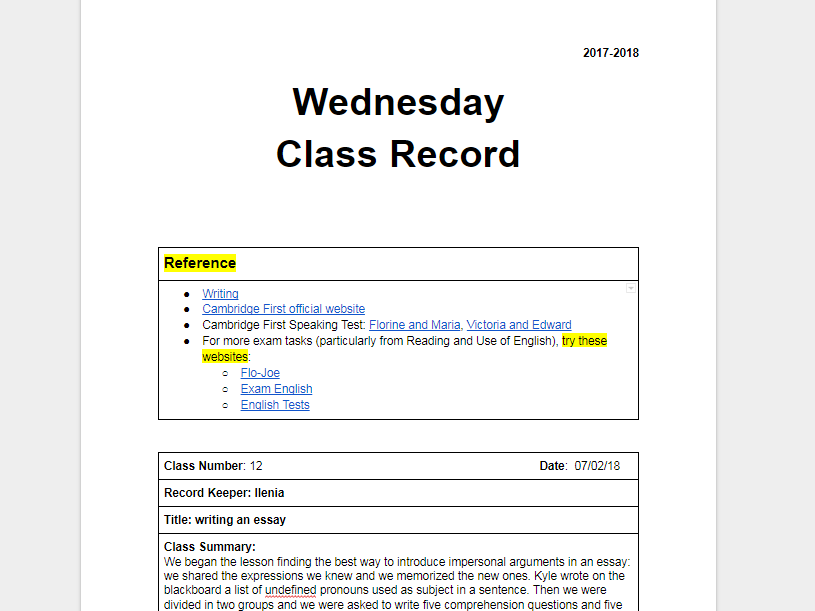

I demo it in class. I just tell them to number their paper 1-10, then give them the list above, then explain what each means, orally. Then, before they it at home individually, I’ll follow up with an email/handout like this:

I demo it in class. I just tell them to number their paper 1-10, then give them the list above, then explain what each means, orally. Then, before they it at home individually, I’ll follow up with an email/handout like this:

BEFORE LISTENING

1. Look: write down basic info like the title, source, speaker, etc-

2. Predict: predict what the speaker might say (topics and vocabulary)

LISTENING

3. Gist listening (once straight through) What’s the speaker’s main point? BLUE pen

4. Detail listening: listen again for more information. This time you don’t have to listen straight through. Advance, pause, skip around, repeat as much as you need. But don’t use the transcript/subtitles yet. BLACK pen

5. 3 tough spots: Identify three spots (minute:second, e.g. 02:45) that are difficult to understand. What’s so difficult? Performance (accent, speed, etc.)? Words (unfamiliar words)? Or non-explicit meaning (you know the words, but not the meaning)?

6. Dictation: Choose a 30-second section of text and transcribe it word for word

7. Check. If there are subtitles/a transcript, listen to check your dictation and understanding. RED pen

AFTER LISTENING

8. Vocab: 5-10 topic-related words that help you talk about the topic, 5-10 new/useful words/expressions

9. Respond: What do you think about the video? Do you agree/disagree? How is it relevant to your life?

10. Reflect: Think back on the listening process

- I understood ____ % after the first listening; ____ % after the detail listening

- What caused the most difficulty? (speed, accent, presentation, topic, vocabulary, etc.)

- Which steps above helped you most understand the listening? (e.g. 1, 4, etc.)

- What should you do more of/less of next time?

Note to the teacher:

The first 4 steps all work together, with each step creating the reason for the next. You look at the YouTube video/webpage and write down some details. This leads to prediction, where students write down what they think the speaker will say (based on their own outside knowledge).

Now, this is not a very exam-useful skill (exam takers have only a short amount of time that they have to spend reading the test items, not predicting – and anyways exams are designed so that outside knowledge shouldn’t be a factor). But it is a very useful life listening skill, and as I said it sets up the point: gist.

In this process, listening for gist is basically checking your predictions. Were you right? And detail listening is checking your gist understanding. Were you right when you listened the first time? What more would you add?

Make sure you tell students they can listen as many times as necessary, backing up, skipping, jumping forward, to get the maximum out of it. That’s detail – real detail.

This is usually the maximum of most listening, but the idea here is to get students to listen further, beyond gist, and start figuring out how the listening is succeeding or breaking down for them.

Ah wait, and the pens. If you can get them to use different colored pens, it’s another way to make the listening visible – to show both them and you how understanding is deepened with each task.

3 Tough Spots

To help students (and you) understand where they aren’t able to decode, have them write down 3 spots and try to determine what made it difficult. This isn’t an exact science, but it will help students try to pinpoint difficulties to get beyond simply “I don’t understand”.

Dictation

Choose a 30” spot and transcribe it word for word. This is way tougher – and takes way longer – than you might think at first (Try it yourself!). The beauty of this is that listening really becomes visible here, as you can see what they hear, and where even their own understanding of English and the topic is not sufficient to compensatorily fill in the gaps in their own decoding.

You might find that while students are getting the content words, they’re missing out on the functional stuff like auxiliary verbs and articles and prepositions that allow listeners to get more than a Swiss-cheese understanding of the content words. And can easily form the basis for many listening lessons to come (stay tuned for the next blog post on that).

Response

This is simply getting students to express why they picked this listening and what they personally learned from it so they can better share in class (or help you understand their choices).

Reflection

Like the tough spots, this part is simply to get students to think about how much they understood and why, so they can think strategically about the listening texts they choose, and what they can do themselves to keep improving.

How do you set it up?

This is really an at-home task. There’s no set-up for me (no writing test questions, yay!), students can choose their own texts, and I just take a peek at the results. But the first time, definitely go through it in class. In a small class, you could have somebody control the computer for a whole class listening. In a bigger class, with equal access to personal tech, you could have everybody listen on their own device with a headset.

Model what you want them to do at home, and let them work in pairs for the dictation and other steps.

When they do it at home, they could either bring in their work next week or (better I think) email it to you – with the link to the audio they listened to. Check to make sure they’ve done it right, and then look into a couple more deeply. What kind of texts did they choose? What were their tough spots? Where there common language features in their dictations?

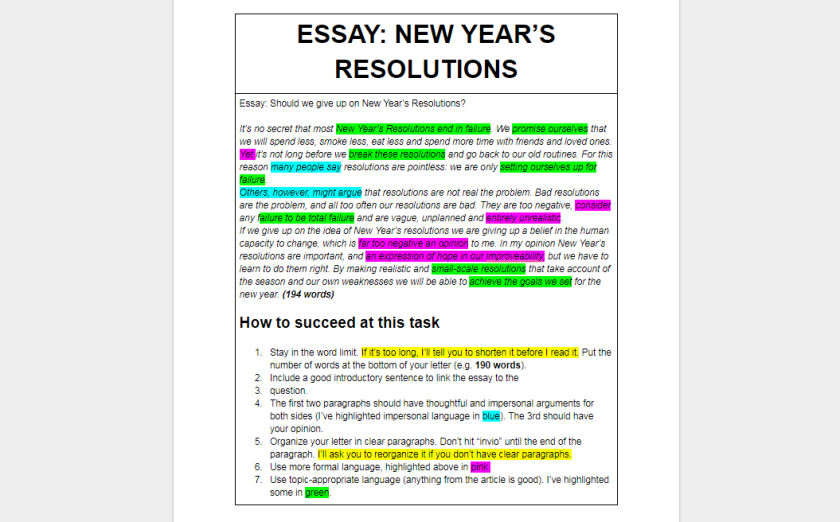

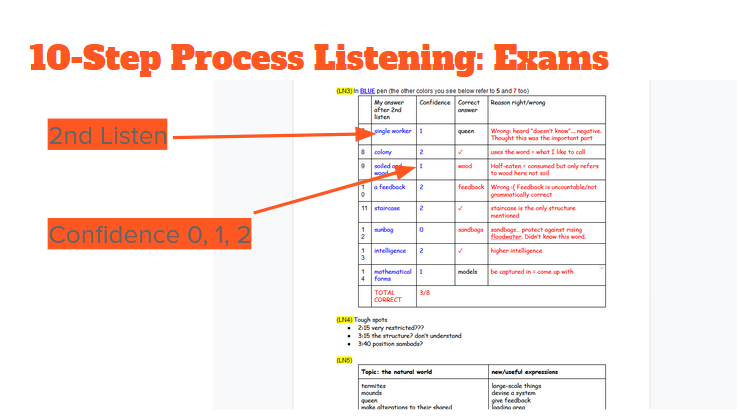

Exam task extension

10-step Process Listening works with YouTube, but it also works with exam tasks as well – and helps you get beyond two-listens-and-done.

In this version, prediction is simply the test strategy of listening, and the first and second listening are played straight through normally. But the rest of the process is kept in place (with a series of steps before students even check their answers – remember, this is not a test, but test prep!).

One feature I add to doing this process with exam tasks is asking students to say how confident they are (0=not at all, 2=confident) with their answer after two listenings. Why?

The one “cognitive style” said to influence exam success is risk-taking (Note: I’ve got a source for this I’ll add soon). In a multiple choice test, where wrong answers are marked the same as no answer, there’s no reason not to guess. But risk-averse people may not do it. Conversely, risk-takers may guess too easily and frequently, confident the odds are on their side as a short-cut to improving their listening. So the idea with putting their confidence level is simply letting them see if their own estimates are correct – while encouraging both types to see the weakness (if any) of their habitual strategy.

If you students are using a test prep coursebook, have them try this at home to go beyond simply chasing after the right answers and get more out of their listening prep.

In the next post I’ll go into some different ways to recycle your listening exam tasks and extend them for teaching.

Tried it out? Let me know!