How-to presentations is an activity cycle that runs for 2½ homework-classwork sessions:

- Homework: listening activity with model text

- Class: model text plus presentation scaffolding

- Homework: write and practice presentation

- Class: deliver presentation

- Homework: reflection on presentation

In part 1 of this article I described the first homework assignment (1), which gets students thinking about presentations.

In part 2, I’m going to describe how I model a presentation and then help students begin to put together theirs (steps 2-3).

2. Class: model text plus presentation scaffolding

You can spend the beginning of the next class discussing the listening text ― as should be obvious, it’s a fairly fertile topic for discussion.

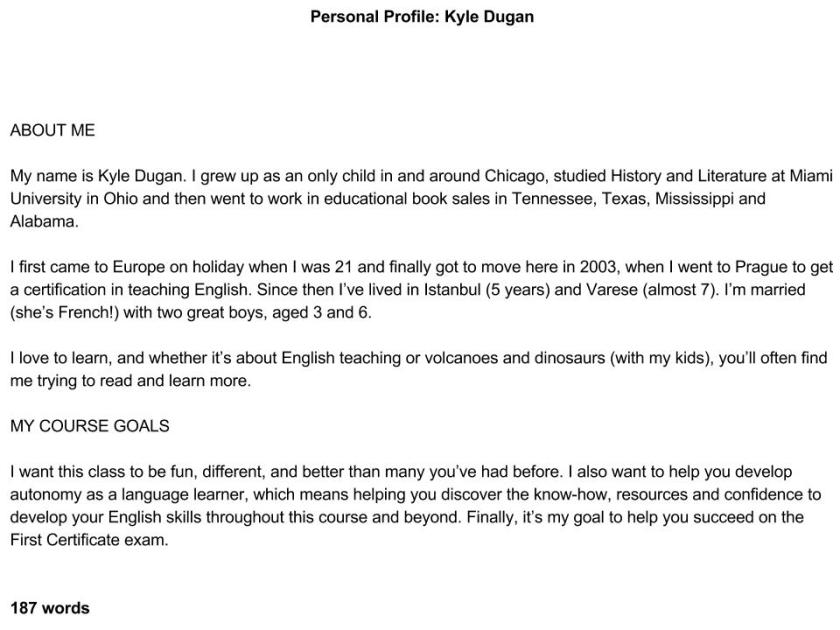

Then you drop the bomb: you expect the students to give their own presentations, next class. But to be fair, you’re not going to ask them to do anything you wouldn’t do yourself. You’re going to give your own How-to presentation.

Here’s the plan:

- First, ask them what they remember from the listening about the elements of a good presentation. Then, have them pull out the activity and check.

- Give the presentation (see below for the text). While listening, students tick off the “best practices” you use.

- Give students a gapfill activity with the “transcript” of the talk and check (see below).

Explanation:

The presentation will model what you expect them to do in the talks, including getting the audience thinking about the topic (or activating schemata, if you will) before the presentation (see part 3 of this series).

I record myself with the built-in voice recorder app on my phone. I strongly encourage you to record yourself giving the presentation, because:

- Many students are terrified of speaking in public, but many students are equally (if not more) put off by the idea of recording and then listening to their own voice. I insist my students record themselves; it’s only fair I do as well.

- It allows them to see (when comparing it with the pre-typed presentation text) that what you produce in a live presentation often goes off-script. In other words, what matters is the presentation you deliver, not whether you say it word-for-word as written.

At the end of your presentation, ask students to write down what they remember, then check in pairs. Then give them the presentation text gapfill and skim it to check. Finally, ask students to do the gapfill.

Finally, check ― by playing back the recording of your presentation (I use either a mini bluetooth speaker or a USB cable to plug into the TV speakers, but your smartphone might have speakers good enough to project, depending on the size of the classroom).

How smoothly the checking process goes depends on how well you’ve memorized the text. Sometimes I written the key gap-fill vocabulary on a piece of paper as cues. But even if you forgot to say some of the keywords in the presentation you’ve delivered, you can still check together.

Just remember to highlight the difference mentioned above between what you intend to say and what you actually say. As long as you deliver the presentation well, it’s usually only the speaker who knows whether or not the text was delivered faithfully.

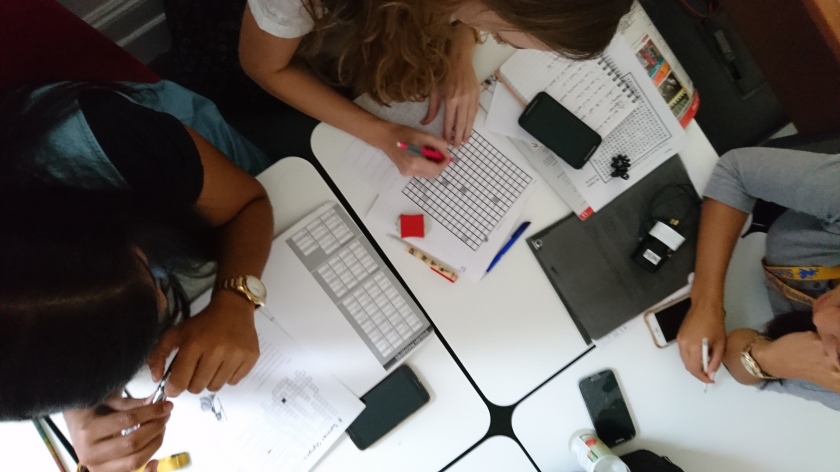

Students build their presentations:

With two models provided (especially your second meta-presentation on the thing itself), students should have ample information for how to construct a how-to presentation. I usually ask them to come up with a topic and 5-paragraph plan, if not the full text, in class. In addition to organization issues, my interventions are often to help them construct an introduction – painting the picture.

3. Homework: write and practice presentation

The homework consists in writing up the presentation and emailing it to me for comments and correction. Make sure to give them a tight deadline ― they’ve got to have time between when you email them the corrections/feedback and the next class in order to practice and memorize the presentation.

In the third and final part of this article, I’ll describe steps 4 & 5, or what to do on the day of the presention – self-recording, self-assessment and post-presentation reflection.

Presentation Model:

How to give a good presentation in English

This is the written text of my presentation. Complete the gaps with the words from below. The first one has been done for you.

eyes delivery engaging attention guarantee repeating connect understand sequencing improve memorable

Today I’m going to talk about how to give a good presentation in English. First, in my talk, I’m going to give you three tips about how you can 1) improve your presentations to make sure you give a presentation that’s interesting, 2)____________ and memorable. So here are my three tips.

The first is that organization is very important. In English we like to have very clear organization to presentations. In the introduction we talk about what we’re going to talk about, and then in the body we talk about the topic itself, and in the conclusion we summarize what we talked about. So it’s a way of both 3)___________ the information and making it clear and easy to understand.

The second tip is to use what’s called “signposting language”. Signposting language is language that helps the audience 4)___________ what’s going to come next, when to pay attention, and to help understand things that they’ve already heard. Some examples of signposting language are introducing something by saying, “Ok, now I’m going to talk about (this).” Other signposting language examples are 5)“_____________ language” to say “First I’m gonna do (this), then I’m gonna do (this), lastly I’m going to do (this)”. Or say, “Now I’ll talk about (this)”. It’s language that’s used to help focus the audience’s 6)___________ on different things.

The last thing that’s important when you’re giving a presentation is the actual physical, 7) ____________ of the presentation. And there’s two things to that. I’d say the first is about speaking. Do you speak in a way that’s clear, slow, easy to understand? And the second is about your body language. Do you look people in the 8)____________? Do you have an open body posture or are you scared and hiding? These things will help your audience—help you 9)__________ with your audience and to make your message clearer.

So, those are my three tips. Remember, organization is important. Use signposting language. And finally, make sure you can deliver your presentation in a way that’s engaging and interesting. If you follow these tips, I 10)___________ that you’ll give better, clearer, more 11)____________ presentations.

Hurdles

Hurdles