What is your first class or first lesson for? Getting to know you? Or just getting through the first page of the coursebook? In Planning Lessons and Courses, Tessa Woodward says that first lessons are an opportunity for:

- Name learning

- Building a sense of community

- Understanding student expectations

- Assessing level

While I agree, I would add three things:

- Materials distribution: Decidedly unsexy, but if you’ve got admin duties like passing out coursebooks you’ve got to schedule time for it.

- Grammatical or lexical improvement: it might sound obvious, but I have previously been guilty of forgetting that students should both learn and practice new language on Day 1, of forgetting that when students think “What did I learn today?” they’ll be thinking in terms of discrete grammar items (and not in terms of community-building).

- Establishing class culture

Number 3, I think, might need some explaining. What is class culture? To paraphrase a great definition from a different context (by Jason Fried, founder of program management app Basecamp), [class] culture is the by-product of consistent behavior. In other words, from how you teach, to what you teach, to how you interact with students and expect them to interact with each other, your class culture will be the result of what you do everyday. Whether your classes are conversation-driven or lockstep by-the-(course)book, whether you’re up scribbling at the whiteboard or hovering over their busily working pairs, whether you’re assigning day one homework or giving them the night off, your first lesson routine should exemplify the principles you teach by. Day one is never a one-off.

And in order to be true to the kind of culture I want to help foster in the classroom, some years ago I decided the best way to start any class is engage with my students, with nothing more than a pen and paper.

My first day routine goes something like this:

PART 1

Take the focus off you with a mingle activity

I really don’t like the me-centric, time-killing forced conversations you go through when waiting for the class to arrive and settle in. So once the proverbial bell rings (or the real one, if you’ve got one), I switch the dynamic, no matter how many students are still missing.

Get up and find three things in common with each of the other people in the class. The following things do not count:

- anything with the words Italy/Italian

- evident physical similarities

- where you live or went to school

Why? I teach mostly monolingual Italians, mostly who come from the provincial city in which I work (which means they mostly go to the same schools). And evident physical similarities ― we both wear glasses, we’re both wearing jeans ― are just too obvious. I want them to dig a little deeper.

“Find X things in common” is great because it forces them to ask questions, and lots of them. And any mingle activity is great because it gives you lots of opportunity to hear them talk, and note down good/improvable language. And as the late arrivals filter in, you can shove them into the mix.

Stop the activity at an appropriate time. While they’re still on their feet, tell them they’re going to have to tell the class what they have in common with other people. And they’re going to have to name names. So give them one last chance to double check names with the people they talked to. Have them sit down. You might want to give them some whole-class feedback about positive/problematic structure, lexis, etc., particularly if you think it will be important in sharing what they have in common. Or you might want to put it on the back burner until later.

Ask everyone to share what they have in common with one other person, introducing that person by name. And tell them to pay attention, because there’ll be a quiz. As the chain of contributions advances, you should repeat the names as much as possible, both for yourself and for the sake of the students.

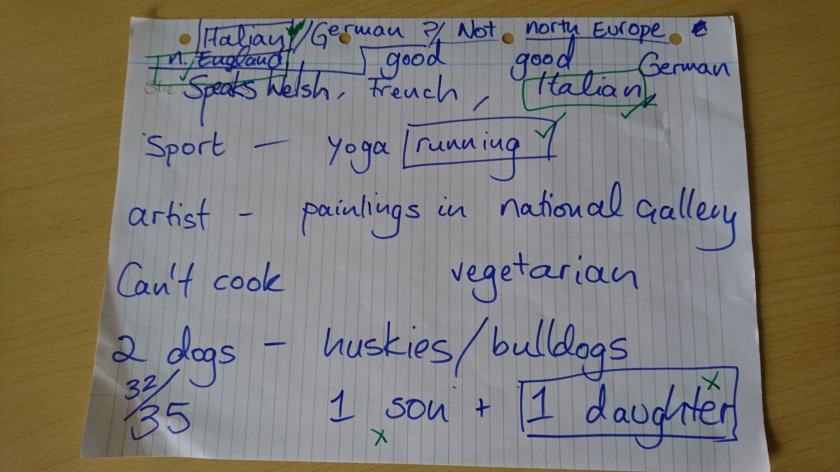

Finally, quiz them: Who studies Engineering? Who also speaks German? Who went to France for holiday? etc.

PART 2

All about me: getting to know the teacher

Now I give them the chance to do what they’ve been dying to, which is find out something about me, the foreigner.

Now, it’s your turn. You can ask me anything you want. Personal, professional, whatever.

There’s usually a moment of silence as everyone (or at least the most courageous) starts mentally scrambling for what to ask. Then I add:

Ok, I’ll give you some help. You’ll have some time to think of the questions you want to ask, and write down the questions. And you can do it in groups.

Put the students into small groups. You’ll want to have at least two.

Write 5 (or 7, or 10 ― in inverse proportion to the number of groups) questions you want to ask me. But your group is your team. The goal is to ask me the original questions. You get a point for each original question you ask. If they other team thinks of the same question, you don’t get a point.

Why? Because, just like my list of too-obvious similarities, this point-per-original-question system eliminates the usual small-talk list of questions. It will give them some often juicier things to remember about you. And it may reveal a lot about their personalities and preoccupations (I’ve had students ask me things like “How many girlfriends have you had?”)

I will, however, give them another chance at the end to ask me anything that we didn’t talk about during the game (where I’m from, etc.).

When they’ve got their list of questions, I say:

You’re going to ask me your questions. But I’ll only answer “grammatically correct” questions (more on this admittedly problematic term in a future post). Double-check to make sure your questions are grammatically correct.

Give them a few minutes to check their questions again (without asking you for help). As they finish checking, ask each group for a team name. I usually suggest silly American-pro-sports-type names like the Jaguars or the Tigers, but they can choose whatever they want.

Let the teams take turns to ask questions, and after you answer them, award one point per original question. Tell groups to shout out if a group reads a question that they’ve also written (in which case no point is awarded).

Dealing with grammatical incorrectness

The best way to deal with a grammatically incorrect questions is simply don’t hear it: play deaf. What? Sorry? What? Students quickly realize they’ve got to reformulate. Give them a number of chances, then help nudge them in the right direction. Then, after you finally “hear” the question and answer it, ask them to repeat the original (as-written) question again and explain the problem.

Getting beyond accuracy

Some other things I “correct” for are appropriacy, register, intonation and idiomaticity. For example, I make it clear that questions like With whom did you go on holiday? are accurate, but sound strangely formal in spoken English. I also make a point about the inappropriacy of the age question (they always ask). Admittedly, if I’m encouraging students to ask me about my past girlfriends on a first meeting, they might as well as me how old I am, too. But does any adult, in any culture, really ask “How old are you?” ― or volunteer that information ― the first time they meet someone?

You can board the problems in shorthand (pres. perf vs. past simple, preposition position in questions, final -s, etc.). When someone makes a similar mistake, help nudge them toward a better question by referring back to the original group who made and explained the mistake ― and let them re-explain it ― or point to the board to show them the problem.

And by boarding such a list, you’re taking the first steps toward creating the kind of grammatical syllabus that addresses their specific needs, not those simply generalized in a course book list.

Follow up

Once you’ve tallied up the points and declared a winner (even though the focus is clearly on the process, and not winning points, it’s still important to keep up the pretense of the game all the way to the end) the first thing I like to do is see what they remember. I say:

Now, with your partners, quickly write down everything you remember about me.

I like including a step like this in any teacher-class or student-class interaction (like presentations) because it allows them to communicatively and communally (re)construct what they’ve learned. And gives those who may not have been paying attention a chance back in.

You can quickly check a few facts, based on their questions (What did I say my most embarrassing moment was?) or let them quiz the other groups.

Turning on each other

Now tell them they’re going to ask each other the questions they’d written for you. Give them a minute to edit their question list ― if any deal with you explicitly as a foreigner, or based on some specific knowledge ― and rewrite those that would inappropriate for their classmates. You can model and then elicit some changed questions.

Monitor and get whole-class feedback, asking each student to share the two or three most interesting things they learned about their partner.

PART 3

Writing: my personal profile

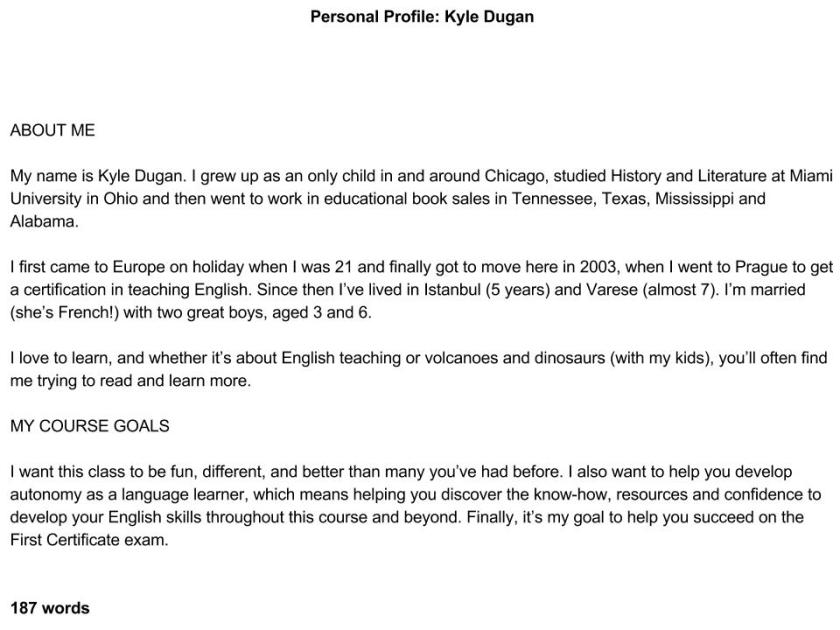

The next step is to get students to write a personal profile. I’ve written my own example as a model. Below is the B2 edition, at Cambridge-First-appropriate 140-190 words. I’ve also got other exam-appropriate editions for other levels. Before giving it to them, I ask:

When would you write a personal profile? (e.g. specific social media contexts)

What info would you include in a personal profile to share with your classmates? (e.g. name, date of birth, reason for taking the class etc.) Board their answers.

Then I hand out my profile:

I tell students to quickly scan for the information thought they might find. What was included? What wasn’t? Then I ask them to check if I’d answered any of the questions from the getting to know me game.

Writing the student profile

The next step is for students to write their own profiles ― whether in class or at home. To get them prepared for the activity, make sure to highlight:

- Organization ― paragraphs, headings, title

- Content ― I want background and course goals, but the specifics are up to them

- Word count, if relevant

Next steps

What do they do with the profile? I text like this is meant to be read by others, so the worst option for you would be to collect them and comment on them in private. Instead, I’d recommend:

- Live carrousel: Students tape their completed texts to the wall. The class circulates and reads. I like to have students comment on other texts in some way to generate more discussion. You can have students put their initials next to things they have in common with the writer, or put their initials + a question mark about something they want to ask. When all the texts have been read, the writer takes down his or her profile and then finds the people who’ve written their initials to discuss commonalities or answer questions. As the teacher, you can underline examples of good and problematic language (you didn’t pick up while monitoring the writing phase) to be discussed in group feedback. But don’t forget to put your initials to commonalities first (sometimes it’s easy to forget that the profile was written for a real purpose ― to introduce the writer to you as a reader ― and that you’re more than just a red pen!)

- Virtual carrousel: Increasingly, I use Google Docs to share class work, and any similar cloud-based document sharing app will do. Essentially, the idea is to have students post their profiles on a shared document, and to leave comments as above. Profile writers can respond in the comments.

Conclusion

As of this writing, that’s my day one routine. Like all great routines, it focuses on the big blocks and leaves lots of room for improvisation where it counts, like getting feedback and working with emergent language (but make sure you plan for the worst, as well). And it, along with my day one reading homework, serves to set expectations for the kind of contributions I expect from the students, and what they can expect from me. And crucially, it’s not a one-off or something to get out of the way, but the foundation for the consistent class culture I hope to establish.

Now, over to you: what’s your day one routine?

References:

Woodward, Terssa. Planning Lessons and Courses. Cambridge University Press, 2001.