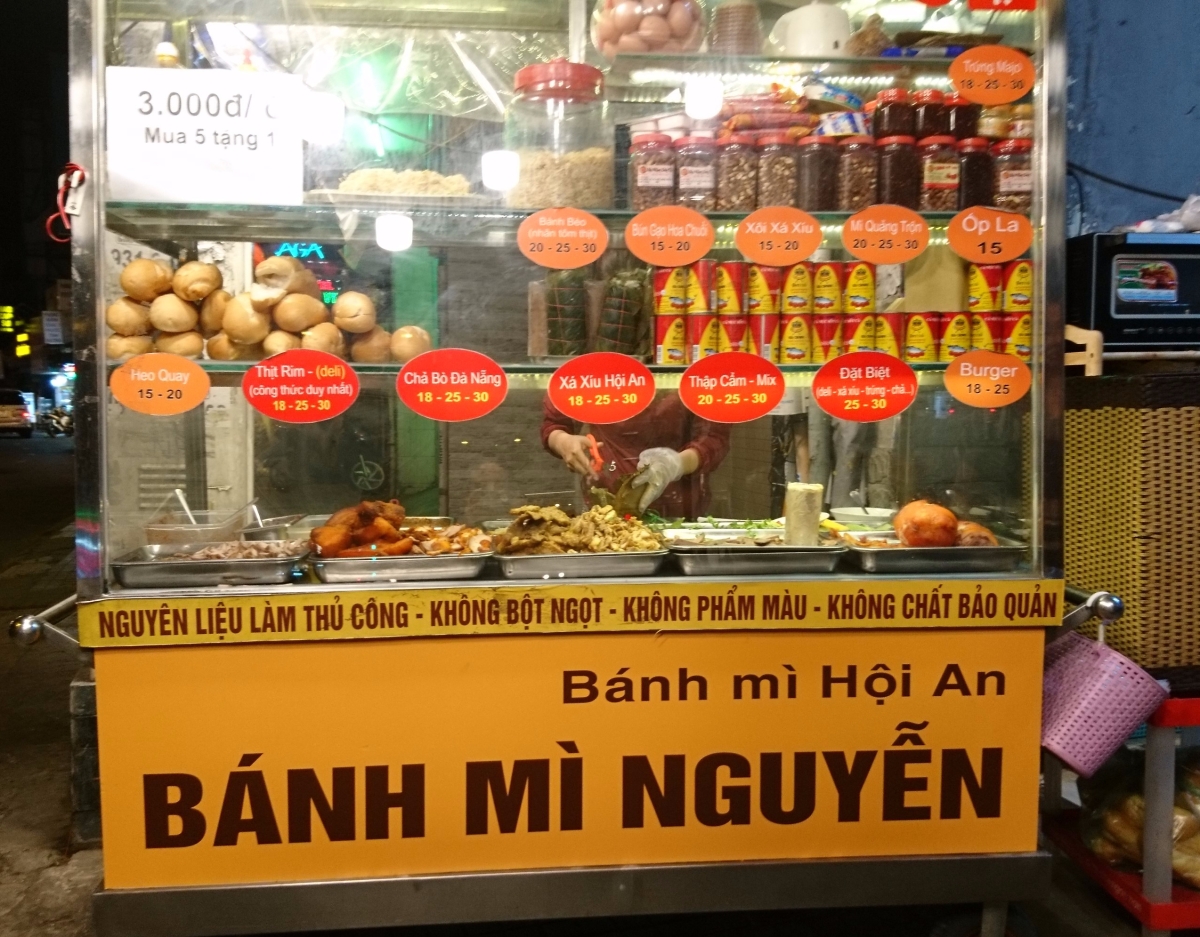

Vietnam was full of surprises, from the amazing food (see gratuitous food porn picture), to being attacked by swarms of motorised humans when attempting to cross the road!

It was actually thanks to a Twitter discussion that I’d found myself hopping onto a plane to Ho Chi Minh City a few months ago. I’d started said thread with the following tweet:

‘It is impossible for a (single) EFL teacher to survive financially without (e.g.) taking a second job or house sharing. Agree or disagree?’.

I’m afraid I can’t embed the tweet here because when the replies started coming in I went on a rant about the injustices of the TEFL industry, then had an attack of what Lindsay Clandfield recently referred to as ‘techlash’ and deleted my account. But thankfully I’m over it now.

The discussion revealed some interesting stuff. On the whole, teachers or ex-teachers who responded agreed that in Europe, especially in the UK, it’s very difficult to make ends meet if you live alone. Several had given up teaching as a result. Those teaching in SE Asia, on the other hand, disagreed, claiming they had a rather comfortable life, actually. Of this part of the world apparently Vietnam is one of the best places in terms of remuneration v. cost of living. So I thought, why not check it out?

I wondered what ELT- like stuff I could do while I was there. I was going for six weeks- so not really long enough to volunteer as a teacher. I decided instead to get in contact with some schools to see if I could do some workshops, rather like the one Kyle and I did at the wonderful ETAS conference and IATEFL Glasgow.

I managed to arrange three workshops in the capital. Two would be with the teachers of Thang Long School, a vocational centre for teenagers, and one would be at the headquarters of ILA, a massive course provider in Vietnam and one which holds regular professional development sessions for local teachers. The former would consist of Vietnamese teachers with local teaching qualifications and some with Master’s degrees, whereas the latter would be an international crowd with CELTA/Delta. I would have about eight teachers at Thang Long, so a chance to do a nice personalised hands-on workshoppy- workshop. My contact at ILA, though, informed me that he had “…invited all the Academic Managers and Teacher Coordinators from HCMC”, about thirty of them apparently.

Yikes. So no pressure, then.

In my next few posts I’ll share a commentary of the workshops, outlining the discussions that arose. Comments are very welcome!

Thang Long School Workshop 1: Teaching writing

Thang Long English Language and Vocational Training School is an NGO-sponsored centre for disadvantaged 16-23 year olds. Many of their students have parents or caregivers without a stable income or with disabilities. The school provides them with free, high quality education thus giving them a better chance for the future.

The teachers had requested that the first workshop be on teaching writing. Since I’m one of those weirdos who actually likes teaching writing, I was full of ideas.

But I had to guess what reasons the teachers had for this request. I came up with these:

- Students lack motivation. They find it difficult to come up with ideas and get started. Writing isn’t cool!

- Marking creates a lot of extra work for the teachers.

- Students don’t necessarily learn from or understand the teacher’s feedback (see Kyle’s post on this)

The Short Story

Out of all the writing genres the short story is my favourite. My interest originates in the years I spent preparing Italian teens for the PET and FCE exams. It had also been the topic of one of my Delta module 2 lessons, actually the one that I failed. I was so distraught afterwards that I told Kyle I just couldn’t face those awful post-lesson critical friend questions – or ‘THE THING’ as we named it – so we just had a few proseccos instead. But despite this, or perhaps because of it, I still love using student-generated stories in the classroom.

If you’ve read other posts on here then you may already know that Kyle and I are great advocates of students creating their own materials. This is because it results in:

- less reliance on the course book (more potential interaction with other Ss)

- personalised content (more cognitive engagement with language)

- individual grading of language according to Ss’ knowledge (suitable for heterogenous classes)

And of course these points all apply to story-writing too, in fact any type of writing, but unlike other genres you have an almost endless range of possibilities to write a story about.

Some may argue that it’s not a common ‘real life’ task, perhaps the reason behind Cambridge removing it as an option in FCE writing part 2. But what about telling anecdotes? Aren’t they just stories in oral form? And learning to write a story before telling it allows more thinking and planning time, which has to be a good thing for our students.

Task 1: Collaborative writing

At the workshop the teachers agreed with my predicted problems (yay!). I managed to glean more information from them too- that most of their learners were CEFR A1- B1, and were young teenagers. Story writing thus seemed appropriate to their age, although Mario Rinvolucri recently said that he teaches even business learners through fairytales. I went ahead with the plan. I started by eliciting the following story components by drawing them on the board:

a flying carpet, a toad, a unicorn, a wishing well, a wizard, a magic mountain

Teachers were put in pairs, chose two of these and wrote a story to include them.

Why? Supplying elements for the story provides scaffolding, as does the brainstorming involved by writing in pairs or team writing. And as I said before, the possibilities for story writing can be endless, so we need to narrow it down a little.

Why a fairytale? Bearing in mind the context, if students were asked to tell a narrative about something personal, they may feel uncomfortable. On top of that, younger learners may be lacking in life experience and not have much to share.

After the pairs had written their stories they swapped, then gave feedback on what they liked about the other story – only positive feedback for the moment.

Task 2: Genre focus: What makes a good story?

Using excerpts from the teachers’ stories we discussed this question and the following three points emerged.

1. The climax

Short stories tend to follow a narrative ‘arc’ of which there are said to be five key points: exposition, conflict, rising action and denouement (see Hale, n.d.). For the very short stories written in the classroom this can be simplified of course. Basically, some problem has to occur, which is resolved at the end in some way. Many students don’t realise this and write stories that go a little bit like:

“I got up and went to school. Then it was lunch break and I talked to my friend. After that I had two more lessons and I went home.”

The teachers’ stories were, of course, much more entertaining. I think one was about Cinderella* not having enough money to buy her groceries and having to ask for help from a talking toad!

2. Flashback

This section of a narrative presents actions occurring before the main events and thus non-chronologically. The following silly examples are mine:

“Cinderella couldn’t buy her groceries because she’d spent all her money on beer the previous night. She’d got so drunk that she fell down the stairs and twisted her ankle. When she woke up in the morning it looked like a tree trunk. Now she was limping pathetically to the corner shop with only 5p in her pocket, hoping that someone would help her.”

This technique of course adds variety to the narrative structure and allows the introduction of information only when it is relevant to the main events.

The start of the flashback is indicated by the past perfect. The writer uses a time expression like ‘now’ to indicate going forward to the ‘present’ time of the story.

3. Dialogue

Dialogue adds depth to the characters and drama to the story. It can be represented by direct speech:

“Please help me, I have a stinking hangover,” Cinderella pleaded.

“Serves you right,” said the toad.

Reporting speech verbs can be used to summarise what was said:

He accused her of being an alcoholic, which she denied.

Or the character’s words can be reported.

She asked him to buy her some more beer. He said he wouldn’t.

It has been suggested that the long and complicated ‘rules’ of transferring direct to reported speech need not be actively taught (see Lewis, 2002). But how many of you know from experience that even (especially?) the most common reporting verbs ‘said’ and ‘told’ cause problems for our students. What other way to practice them in written contextualised form but in a story?

Discussion:

The teachers asked a couple of questions.

- In a flashback scene why is the past perfect only used at the beginning?

Using the past perfect for the whole of the scene, especially if it’s a long one, would be awkward (see Kress, 2008). Compare:

“Cinderella couldn’t buy her groceries because she’d spent all her money on beer the previous night. She’d got so drunk that she’d fallen down the stairs and had twisted her ankle. When she had woken up in the morning it had looked like a tree trunk. Now she was limping pathetically to the corner shop with only 5p in her pocket, hoping that someone would help her.”

Which one sounds better?

2. Can you use the present perfect in a story?

Hmmm. Not in the narrative, since it’s not a narrative verb form. But you can use it in direct speech, or as the ending phrase or coda, e.g.

“I’ve never been so embarrassed in my life!”

Focus on the writing process

All writing, indeed like this blog post, needs to be revised, edited and proof-read, before being submitted/published. In the classroom, however, this is often overlooked. Learners submit work which is actually a first draft. In my experience, teenagers in particular will expect the improvement of the text to be done by the teacher. But is it useful? They seem to pay very little attention to their written work once it’s been corrected. Time elapsed between the input session, the writing of the text, handing it in, the teacher marking it, and the student reading the corrections, can also make teacher correction ineffectual, since the writing process is no longer fresh in the student’s mind. (see Hedge,2000).

The process approach to teaching writing is a potential solution. Keeping it very simple, it goes something like this (apologies for low-tech image and free advertising).

There could be more arrows here. For example, the final version might be given back to the student for revising. After revising, you may need to go back to brainstorming new ideas etc. etc. Some of the teachers at Thang Long were already familiar with these processes, so I was able to elicit the stages. However, they admitted that they did not use it in class and that the writing task was usually set as homework and handed in for marking the next lesson. They also feel pressure to correct all of the student’s mistakes. Assignments were handwritten on paper since their students don’t have access to laptops.

Elements of process writing could therefore be used to resolve the three teacher issues with teaching writing. Its collaborative nature scaffolds the task (problem 1) while also putting the onus on the students to correct their own work (problem 2).

With the advent of technology, process writing could be criticised as outdated since now there is a plethora of apps that could do the job of proofreading for you, and even correct your grammar mistakes. But as my experience at Thang Long school shows, there are still countless contexts around the world in which technology is an unattainable luxury.

Pure process writing, of course, does not take into account the genre-specific elements of task 1, since it focuses on how the learner is writing, rather than the product, or what the learner is writing. This is why I use a combination of approaches which takes into consideration the function of the text, what Badger and White (2000) call ‘Process-Genre’.

Task 3: Collaborative correction

To deal with teacher-problem 3 my suggestion was to use a marking code. I have a Google Doc link to my code that I share with my students which explains how it works. I had the teachers practise using it with some samples of students’ stories.

A marking code is nothing revolutionary of course, but teachers may fear that stakeholder expectations won’t be met if students are asked to correct their own work. My aim was therefore to give the teachers confidence and tell them what I wish someone had told me when I started teaching: “It’s OK!”. That is, actually, it’s BETTER for the students to work harder to understand where they went wrong. It’s also OK for the teacher to find a way to make their workload lighter. I remember it took me years to realise that my energy would be much better spent on teaching a lesson, rather than spending hours preparing it and being exhausted before it started!

Discussion:

About the correction code and the revision process. Doesn’t it create more marking?

Actually this a good point. If a class of 20 re-submit their work, then it would appear that there is more marking to do not less. My advice is to give fewer writing tasks, spending much more time revising the same piece and do so in the lesson.

What if they don’t understand what the mistake is?

You should only use the marking code for language points that you know your student should know. These are mistakes rather than errors – features of the learners current level or stage of interlanguage.

Should we correct everything?

No. This would be demotivating and creates more work for you. Correct the most important things such as what they’ve already studied or something that makes the text difficult to understand. You should give some positive feedback too.

Should the students use it to correct each other’s work?

Yes, why not. But they would need training in this, and a simplified version could be used. The good thing about this of course is the language discussion that would come up. Careful though because their corrections might not be right! So you would need to monitor closely and use reference materials.

Round up – Solutions to the teachers’ problems:

1. Scaffold the task by process stages of brainstorming ideas. Personalise the tasks. Team/pair-writing.

2. Use a correction code. Have students peer and self correct.

3. Do writing correction in the lesson. Use peer correction. Keep working at the same piece for longer.

My last thought was this:

Remember…it is the students who should be doing most of the work to improve their writing NOT THE TEACHER! 🙂

(*Note: I did not use a picture of Cinderella since I object to the fact that she is always portrayed as white, blond, skinny, not to mention pathetic, seeing as she has to be ‘saved’ by a guy. I much prefer the idea of her going out partying and meeting talking toads in the forest.)

References:

Badger, R., White, G. (2000). A process genre approach to teaching writing. ELT Journal, Volume 54, Issue 2, April 2000, Pages 153–160,

Hale, A. (n.d.). How to Structure a Story: The Eight Point Arc. Retrieved from: http://www.dailywritingtips.com/how-to-structure-a-story-the-eight-point-arc/

Hedge, T. (2000). Teaching and Learning in the Language Classroom. Oxford: OUP

Kress, N. (March 11, 2008) 3 tips for writing successful flashbacks. Retrieved from: http://www.writersdigest.com/qp7-migration-all-articles/qp7-migration-fiction/3_tips_for_writing_successful_flashbacks

Lewis, M. (2002). The English Verb. Boston MA:Thomson Heinle